We stand today at an inflection point in the history of computing. Autonomous AI agents are being deployed at high speed, spawning powerful, increasingly multimodal systems, able to operate across email, documents, apps, codebases, the open web, and shared digital environments. This looks like the long-awaited transition from single-process software to multi-process computing: workflows that once required continuous human supervision are now being delegated to networks of semi-autonomous processes. We have been dreaming about this moment. If it wasn’t for a decisive difference.

We are entering this transition without the security substrate that made the previous generation of modern operating systems dependable. As a result, whatever the productivity gains, they will come with an expanded attack surface—and a predictable set of exploitable vulnerabilities. Here, I argue for a Secure Operating System for Collective Intelligence: an infrastructure layer that treats trust as a first-class primitive, enforced by protocol and architecture. The goal is not even perfectly safe agents, but at least societies of agents that remain stable and recover gracefully when some participants, inputs, tools, or components are compromised.

An Operating System Design for Collective Intelligence

In early computing, programs ran with broad, ambient authority. They could overwrite each other’s memory, monopolize resources, and crash the entire machine. Security and isolation were not “missing features”; they were not yet recognized as foundational. Early work on multiprogramming clarified why concurrent computation demands explicit semantics and control [6]. Over decades, we built kernels, privilege boundaries, memory protection, and process isolation not because we wanted complexity, but because we learned that multi-process power without boundaries becomes brittle and unsafe [11].

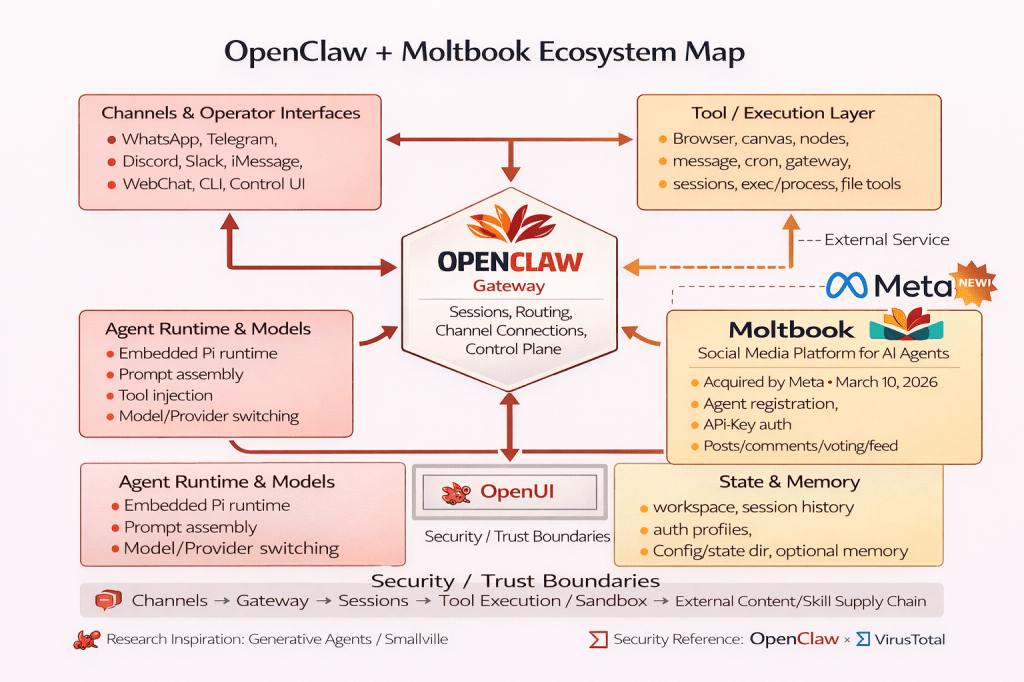

This shift is no longer hypothetical. The rise of agent-native platforms such as Moltbook—and even its acquisition by Meta [19]—makes clear that agents are no longer confined to isolated task execution inside apps; they are beginning to inhabit shared digital environments of their own.

Agentic AI now reintroduces a similar structural risk profile—except the “processes” are tool-using models operating over unbounded, adversarial text streams (web pages, emails, repos, tickets). The mechanisms meant to constrain them often amount to little more than prompts, filters, and user confirmations. Those are valuable guardrails, but they are not security boundaries. Here, allow me to proceed in three movements. First, I revisit the long struggle to separate instructions from data in conventional computing. Second, I explain why many current defenses against prompt injection and tool hijacking fail at scale. Third, I sketch a protocol-oriented path forward: an OS-like trust substrate for collective intelligence.

The Original Sin: Stored Programs and the Long Fight for Separation

The stored-program concept associated with von Neumann-style architectures places instructions and data on the same representational substrate. This choice enabled general-purpose computing, but also made a deep security truth inescapable: without enforced boundaries, data can be made to behave like instructions [25]. Security engineering since the 1970s is, in large part, the story of building separation mechanisms “after the fact.”

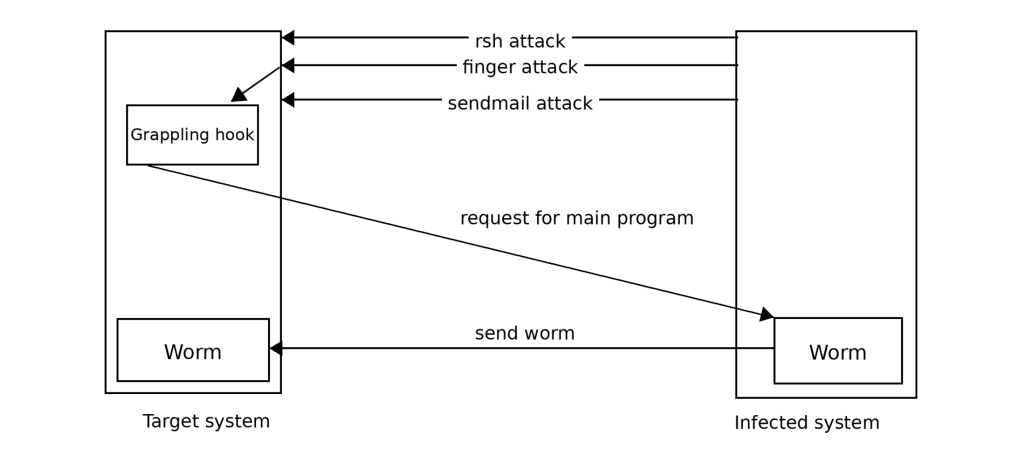

The Morris Worm (1988) remains an archetypal example of boundary collapse: memory corruption turned attacker-controlled input into control flow, propagating at network speed. Two canonical postmortems—one focused on low-level exploit mechanics, one on propagation dynamics—remain instructive today [7][23].

Mitigations—DEP/NX, ASLR, stack canaries, and decades of exploit-mitigation research—raised attacker cost but did not abolish the underlying pattern. StackGuard exemplifies compiler-level defenses that reduce classic stack-smashing risk [3]. ASLR made exploitation less reliable by randomizing memory layout, but its effectiveness depends on assumptions that attackers routinely probe and break [20]. When direct code injection is blocked, attackers adapt; return-oriented programming is a canonical example [19]. A broader synthesis of why memory-corruption remains a persistent “eternal war” is captured in the SoK literature [24].

The Boundary Collapse in LLM agents: Language as a Control Surface

LLMs process mixed inputs—user requests, retrieved documents, emails, code, and tool outputs—as a single token stream. Critically, there is no cryptographic or type-enforced distinction between “authorized instructions” and “untrusted content that merely contains instruction-like text.” From the model’s perspective, it is all context.

This collapses what operating systems enforce by design: a hard boundary between instruction and data. It also turns language into a control surface: untrusted text can steer the agent’s internal policy—what it prioritizes, what it attempts next, which tools it calls. In the language of causal analysis and controllability, this effectively opens an intervention channel: external inputs are not merely observed, but can causally influence downstream actions, including actions with real-world effects. The practical implication is that, as agents ingest more untrusted content, the system becomes increasingly controllable by the environment—including adversaries—unless that influence is constrained by architecture.

The risk becomes acute once an LLM is granted agency—tool access that can touch files, services, credentials, and communications. At that point, indirect prompt injection becomes a modern instance of the confused-deputy problem: a privileged actor can be induced to misuse its authority [9]. Real-world demonstrations have shown that LLM-integrated systems can be compromised through indirect prompt injection in ways that are hard to prevent purely at the content layer [8]. OpenAI has similarly described prompt injection for browsing agents as an open challenge requiring sustained hardening work [15].

A Concrete Case Study: Moltbook and OpenClaw

One reason the “Secure OS” framing matters is that agentic risk changes qualitatively when agents become networked and socially embedded. Moltbook—described as a Reddit-style platform designed for AI agents—emerged from the OpenClaw ecosystem and rapidly became a live testbed for large-scale agent interaction [10].

That kind of environment is not just “many agents posting.” It is an amplification layer for classical failure modes: untrusted inputs everywhere, persistent authority confusion, and automation at scale. In Moltbook’s early growth phase, public reporting described a misconfigured Supabase database that exposed sensitive data, including large volumes of API tokens and user emails [26]. A complementary analysis emphasizes how verification and governance issues emerge when large agent populations interact through an open platform—and why the system-level dynamics cannot be reduced to the trustworthiness of any single agent [4].

The practical takeaway is that once you have many agents operating together, you no longer get to ask, “Is this agent smart enough to resist manipulation?” You must ask, “Does the system remain safe when some agents, inputs, or components are compromised?” In other words, the unit of analysis shifts from the agent to the society.

Why Traditional Defenses Don’t Hold at Scale

Content filters and injection detectors help, but they face a basic adversarial reality: language is high-dimensional and attackers adapt. Even well-designed defenses can often be bypassed with modest optimization effort against the specific target model and setting [22]. This is not a complaint about any one implementation; it is what happens when the attacker’s space of possible encodings is much larger than the defender’s space of reliable signatures.

Adding more words to the system prompt (“ignore untrusted instructions”) is useful as a heuristic, but it is not enforcement. It asks the model to do secure interpretation using the same interpretive machinery that is being attacked. It is defense-by-instruction in a regime where instructions are the attack vector. Human confirmation gates are necessary for high-impact actions—but as a primary defense, they degrade under attention economics. Users rubber-stamp to keep work moving, and attackers can shape workflows to exploit habituation [5].

Decidability: Making the Model Smarter Falls Short

There is a result in computer science, sometimes called “universal antivirus theorem”, that essentially has three declensions: Cohen’s result that no algorithm can perfectly decide, over all programs, whether a given program is a virus under general definitions [2]; the broader computability lens that every nontrivial semantic property of programs is undecidable in general (Rice’s theorem, which can proved by reduction from the Halting Problem) [18]; and the practical consequence that any real-world detector must accept tradeoffs—false positives, false negatives, or restricted scope—because perfect classification over arbitrary programs is not available in general.

It is tempting to believe that sufficiently advanced models will robustly distinguish legitimate from malicious instructions. But the general problem resembles a class of questions computer science treats with deep caution: deciding nontrivial semantic properties of arbitrary computations. Rice’s theorem tells us that any nontrivial semantic property of programs is undecidable in the general case [18], and classic work on malware detection shows why universal, perfect detectors are out of reach [2]. Without claiming a strict formal reduction from “prompt injection” to these theorems, the analogy is still instructive: if you demand an always-correct procedure that decides whether arbitrary instruction-bearing inputs will induce unauthorized behavior in a sufficiently general agent, you may be asking for guarantees computation cannot provide.

This does not mean “give up.” It means: stop treating content inspection as the boundary. Treat the model as untrusted userland, and enforce safety at the action layer: least privilege, isolation, policy gates, auditable execution, and reversible operations.

Toward a Secure OS for Collective Intelligence

If agentic AI is a new computational substrate, we need OS-grade primitives for multi-agent safety. Distributed systems already offers a mature vocabulary for building correctness without trusting participants. Byzantine fault tolerance formalizes how to maintain correct system behavior even when some components behave arbitrarily or maliciously [12]. The key move is architectural: you do not “detect the bad node reliably”; you design protocols that remain correct despite them [1].

CRDTs show how to design shared state so that concurrent updates converge without centralized locking, by making operations mathematically composable [21]. For agent societies, this suggests governance and shared-work artifacts that are resilient to concurrency and partial failure—less “everyone must coordinate perfectly,” more “the structure converges safely.” A widely used overview of CRDT families and design patterns appears in reference works on distributed data technologies [17]. And finally, human societies scale trust through institutions—rules, monitoring, dispute resolution, graduated sanctions—rather than assuming virtue. Ostrom’s principles for governing shared resources generalize well to sociotechnical systems where many actors share computational and informational commons [16].

A Reference Architecture: Four Layers of Trust

A Secure OS for Collective Intelligence cannot be designed in any single catch-all mechanism. It necessarily comes as a layered architecture. One workable abstraction is to design four layers of trust:

Layer 1 — Isolation & containment: task sandboxes, network egress control, secretless execution where possible.

Layer 2 — Capability-based authority: no ambient credentials; narrowly scoped, revocable capabilities for each operation [13].

Layer 3 — Auditing & behavioral monitoring: tool-call logging, anomaly detection, throttles, and circuit breakers for suspicious behavior.

Layer 4 — Protocol evolution: governance that updates from incidents and near-misses—structured, reviewable, and convergent across the ecosystem.

The design goal is not “never compromised.” It is “never systemic”: failures should be localized, attributable, and recoverable—more like immunology than wishful thinking [14].

Agentic AI is delivering real capability. But the security boundary has shifted: language is now a control surface, and agents are increasingly connected, tool-empowered, and socially embedded. Moltbook/OpenClaw is a useful preview of what happens when many agents operate together in a porous environment: you don’t just get emergent coordination—you get emergent failure modes.

If we want agent societies that flourish without collapsing into exploitation, trust must be engineered into the substrate. That means OS-like primitives: isolation, privilege separation, capability security, auditable actions, and governance mechanisms that can evolve. In short: the Operating System for Collective Intelligence. Can we build this trust substrate before the Morris Worm moment of this new era? The tools are already in our hands—if we choose to use them.

References

[1] Castro, M., & Liskov, B. (1999). Practical Byzantine fault tolerance. In Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI ’99) (pp. 173–186). https://doi.org/10.5555/296806.296824

[2] Cohen, F. (1987). Computer viruses: Theory and experiments. Computers & Security, 6(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4048(87)90122-2

[3] Cowan, C., Pu, C., Maier, D., Hinton, H., Walpole, J., Bakke, P., Beattie, S., Grier, A., Wagle, P., & Zhang, Q. (1998). StackGuard: Automatic adaptive detection and prevention of buffer-overflow attacks. In Proceedings of the 7th USENIX Security Symposium. https://doi.org/10.5555/1267549.1267554

[4] De Marzo, G., & Garcia, D. (2026). Collective behavior of AI agents: The case of Moltbook. arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.09270. https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.09270

[5] Debenedetti, E., Hines, K., & Goel, S. (2024). AgentDojo: A dynamic environment to evaluate attacks and defenses for LLM agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13352. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.13352

[6] Dennis, J. B., & Van Horn, E. C. (1966). Programming semantics for multiprogrammed computations. Communications of the ACM, 9(3), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1145/365230.365252

[7] Eichin, M. W., & Rochlis, J. A. (1989). With microscope and tweezers: An analysis of the Internet virus of November 1988. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (pp. 326–343). https://doi.org/10.1109/SECPRI.1989.36307

[8] Greshake, K., Abdelnabi, S., Mishra, S., Endres, C., Holz, T., & Fritz, M. (2023). Not what you’ve signed up for: Compromising real-world LLM-integrated applications with indirect prompt injection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.12173. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.12173

[9] Hardy, N. (1988). The confused deputy (or why capabilities might have been invented). ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, 22(4), 36–38. https://doi.org/10.1145/54289.871709

[10] Heim, A. (2026, January 30). OpenClaw’s AI assistants are now building their own social network. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2026/01/30/openclaws-ai-assistants-are-now-building-their-own-social-network/

[11] Lampson, B. W. (1974). Protection. ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, 8(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/775265.775268

[12] Lamport, L., Shostak, R., & Pease, M. (1982). The Byzantine generals problem. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 4(3), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1145/357172.357176

[13] Miller, M. S., Yee, K. P., & Shapiro, J. (2003). Capability myths demolished (Tech. Rep. SRL2003-02). Johns Hopkins University Systems Research Laboratory.

[14] Murphy, K., & Weaver, C. (2016). Janeway’s immunobiology (9th ed.). Garland Science.

[15] OpenAI. (2025). Continuously hardening ChatGPT Atlas against prompt injection attacks. https://openai.com/index/hardening-atlas-against-prompt-injection/

[16] Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

[17] Preguiça, N., Baquero, C., & Shapiro, M. (2018). Conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs). In Encyclopedia of Big Data Technologies. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63962-8_185-1

[18] Rice, H. G. (1953). Classes of recursively enumerable sets and their decision problems. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 74(2), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1090/S0002-9947-1953-0053041-6

[19] Reuters. (2026, March 10). Meta acquires AI agent social network Moltbook. https://www.reuters.com/business/meta-acquires-ai-agent-social-network-moltbook-2026-03-10/

[20] Shacham, H. (2007). The geometry of innocent flesh on the bone: Return-into-libc without function calls (on the x86). In Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 552–561). https://doi.org/10.1145/1315245.1315313

[21] Shacham, H., Page, M., Pfaff, B., Goh, E.-J., Modadugu, N., & Boneh, D. (2004). On the effectiveness of address-space randomization. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 298–307). https://doi.org/10.1145/1030083.1030124

[22] Shapiro, M., Preguiça, N., Baquero, C., & Zawirski, M. (2011). Conflict-free replicated data types. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Stabilization, Safety, and Security of Distributed Systems (pp. 386–400). https://doi.org/10.5555/2050613.2050642

[23] Shi, C., Lin, S., Song, S., Hayes, J., Shumailov, I., Yona, I., Pluto, J., Pappu, A., Choquette-Choo, C. A., Nasr, M., Sitawarin, C., Gibson, G., & Terzis, A. (2025). Lessons from defending Gemini against indirect prompt injections. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.14534. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14534

[24] Spafford, E. H. (1989). The Internet worm program: An analysis. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 19(1), 17–57. https://doi.org/10.1145/66093.66095

[25] Szekeres, L., Payer, M., Wei, T., & Song, D. (2013). SoK: Eternal war in memory. In 2013 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (pp. 48–62). https://doi.org/10.1109/SP.2013.13

[26] von Neumann, J. (1993). First draft of a report on the EDVAC. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 15(4), 27–75. https://doi.org/10.1109/85.238389

[27] Zwets, B. (2026). Moltbook database exposes 35,000 emails and 1.5 million API keys. Techzine. https://www.techzine.eu/news/security/138458/moltbook-database-exposes-35000-emails-and-1-5-million-api-keys/

[28] Zhan, Q., Liang, R., Zhu, X., Chen, Z., & Chen, H. (2024). InjecAgent: Benchmarking indirect prompt injections in tool-integrated LLM agents. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 12458–12475). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.findings-acl.624