As AI continues to evolve, conversations have started questioning the future of traditional programming and computer science education. The rise of prompt engineering—the art of crafting inputs to lead AI models to generating specific outputs—has led many to believe that mastering this new skill could replace the need for deep computational expertise. While this perspective does capture a real ongoing shift in how humans interact with technology, it overlooks the essential role of human intelligence in guiding and collaborating with AI. This seems a timely topic, and one worthy of discussion—one that we’ll be exploring at this year’s Cross Labs Spring Workshop on New Human Interfaces.

The Evolving Role of Humans in AI Collaboration

Nature demonstrates a remarkable pattern of living systems integrating new tools into, transforming them into essential components of life itself. For example, mitochondria, once an independent bacteria, became integral to eukaryotic cells, taking the function of energy producers through endosymbiosis. Similarly, the incorporation of chloroplasts enabled plants to harness sunlight for photosynthesis, and even the evolution of the vertebrate jaw exemplifies how skeletal elements were repurposed into functional innovations. These examples highlight nature’s ability to adapt and integrate external systems, offering a profound analogy for how humans might collaborate with AI to augment and expand our own capabilities.

Current AI systems, regardless of their sophistication, remain tools that require some kind of human direction to achieve meaningful outcomes. Effective collaboration with AI involves not only instructing the machine but also understanding its capabilities and limitations. Clear communication of our goals ensures that AI can process and act upon them accurately. This process transcends mere command issuance; it quickly turns into a dynamic, iterative dialogue where human intuition and machine computation synergize to mutually cause a desirable outcome.

Jensen Huang’s Take on Democratizing Programming

NVIDIA Founder and CEO Jensen Huang highlighted this paradigm shift in these words:

“The language of programming is becoming more natural and accessible. With AI, we can communicate with computers in ways that align more closely with human thought. This democratization empowers experts from all fields to leverage computing power without traditional coding.”

The quote is from a couple of years ago, in Huang’s Computex 2023 keynote address. This transformation means that domain specialists—not just scientists and SWEs—can now harness AI to drive their work forward. But this evolution doesn’t render foundational knowledge in computer science obsolete; it merely underscores the imminent change in the nature of human-machine interactions. Let us dive further into this interaction.

Augmenting Human Intelligence Through New Cybernetics

A helpful approach, to fully realize AI’s potential, is to focus on augmenting human intelligence via ways akin to the infamous ways of cybernetic technology (Wiener, 1948; Pickering, 2010). « Infamous » only because of how the field abruptly fell out of favor in the late 70’s, as the time’s technical limitations unfortunately led to its decline, along with a growing skepticism about its implications for agency, autonomy, and human identity. They were nevertheless not a poor approach by any count, and may soon become relevant again, as technology evolves into a substrates that better supports its goals.

Such cybernetic efforts towards human augmentation aim to couple human cognition with external entities such as smart sensors, robotic tools, and autonomous AI models, through a universal science of dynamical control and feedback. This integration between humans and other systems fosters an enactive and rich, high-bandwidth communication between humans and machines, enabling a seamless exchange of information and capabilities.

Embedding ourselves within a network of intelligent systems, and possibly other humans as well, enhances our cognitive and sensory abilities. Such a symbiotic relationship would allow us to better address complex challenges, by efficiently processing and interpreting vast amounts of data. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are examples of such technologies that facilitate direct communication between the human brain and external devices, offering promising avenues for cognitive enhancement (Lebedev & Nicolelis, 2017). Another example is augmented reality (AR), which overlays real-world percepts and virtual knobs with digital additions to enhance human’s connections to physical reality, thus enhancing our experience and handling of it (Billinghurst et al., 2015; Dargan et al., 2023). If they manage to seamlessly blend physical and virtual realities, AR systems have the power to amplify human cognitive and sensory capabilities, empowering us to navigate our problem spaces in contextually meaningful yet intuitive ways.

Humble Steps: The Abacus

We just mentioned a couple of rather idealized, advanced-stage technologies to cybernetically couple humans to new rendering of the reality of problem spaces they navigate. But a new generation of cybernetics need not start at the most complex and technologically advanced level. In fact, the roots of such a technology can already be found in simple, yet powerful and transformative tools such as the abacus. That simple piece of wood, beads, and strings has done a tremendous job externalizing our memory and computation, extending our mind’s ability to process numbers and solve problems. In doing so, it has demonstrated how even the most modest-looking tool may amplify cognitive abilities in such a groundbreaking way, laying the basis for more sophisticated augmentations that may merge human intelligence with machine computation.

Not only did the abacus extend human mathematical abilities, but it did so by enactively—through an active, reciprocal interaction—stretching our existing mechanisms of perception and understanding, enhancing how we sense, interpret, interact with, and make sense of the world around us. The device doesn’t replace, but instead really amplifies our existing innate sensorial mechanisms. It brings our mathematical cognitive processes into a back-and-forth ensemble of informational exchanges between our inner understanding and the tool’s mechanics, through which we effectively—and, again, enactively—extend. Similarly, today’s cybernetic technologies can start as modest, focused augmentations—intuitive, accessible, and seamlessly integrated—building step by step toward more profound cognitive symbiosis.

Extending One’s Capabilities Through Integration of Tools

The principle of extending human capabilities through tools, as exemplified by the abacus, can be generalized in a computational framework, where integrating various systems may enhance their combined power to solve problems. Let’s take a simple example of such phenomenon. For instance, in Biehl and Witkowski (2021), we considered how the computational capacity of a specific region in elementary cellular automata (ECA) can be expanded in terms of the number of functions it can compute.

Interestingly, this research led to the discovery that while coupling certain agents (regions of the ECA) with certain devices they may use (adjacent regions) typically increases the number of functions they are able to compute, some strange instances would occur as well. Sometimes, in spite of « upgrading » the devices used by agents (enlarging the adjacent regions to them), the computing abilities of the agents ended up dropping instead of increasing. This is the computational analog to people upgrading to a new phone, a more powerful laptop, or a bigger car, only to end up being behaviorally handicapped by this very upgrade.

This shows how this mechanism of functional extension, much like the abacus’s amplification of human cognition, extends nicely to a large range of situation, and yet should be treated with great care as it may affect greatly the agency of users. Now that we have established the scene, let’s dive into the specific and important tool of programming.

Programming: Towards A Symbiotic Transition

Programming. What an impactful, yet fundamental tool invented by humans. Was it even invented by humans? The process of creating and organizing instructions—which can later be followed by oneself or a distinct entity to carry out specific tasks—can be found in many instances in nature. DNA encodes genetic instructions, ant colonies use pheromones to dynamically compute and coordinate complex tasks, and even « simple » chemical reaction networks (CRNs) display many features of programming, as certain molecules act as instructions that catalyze their own production, effectively programming reactions that propagate themselves when specific conditions are met. Reservoir computing would be a recent example of this ubiquity of programming in the physical world.

Recently, many have argued that it may no longer be worthwhile to study traditional programming, as prompt engineering and natural language interactions dominate. While it’s true that the methods for working with AI are changing, the essence of programming—controlling another entity to achieve goals—remains intact. Sure, programming will look and feel different. But has everyone forgotten how far we’ve come since the advent of Ada Lovelace’s pioneering work and the earliest low-level programs? Modern software engineering typically implies working with numerous abstraction layers built atop the machine and OS levels—using high-level languages like Python, front-end frameworks such as React or Angular, and containerization tools like Docker and Kubernetes. This doesn’t have to be seen as so different from the recent changes with AI. At the end of the day, in one way or another, humans must utilize some language—or, as we’ve established, a set of languages at different levels of abstractions—to combine their own cognitive computation with the machine’s—or, other humans too, really, at the scale of society—so as to work together to produce meaningful results.

This timeless collaboration—akin to the mitochondria or chloroplast story we touched on earlier—will always involve the establishment of a two-way communication. On one hand, humans must convey goals and contexts to machines, as AI cannot achieve objectives without clear guidance. On the other, machines must send back outputs, whether as solutions, insights, or ongoing dialogue, refining and improving the achievement of goals. This bidirectional exchange is the foundation of a successful human-machine partnership. Far from signaling the end of programming, it signals its natural evolution into a symbiotic relationship where human cognition and machine computation amplify one another.

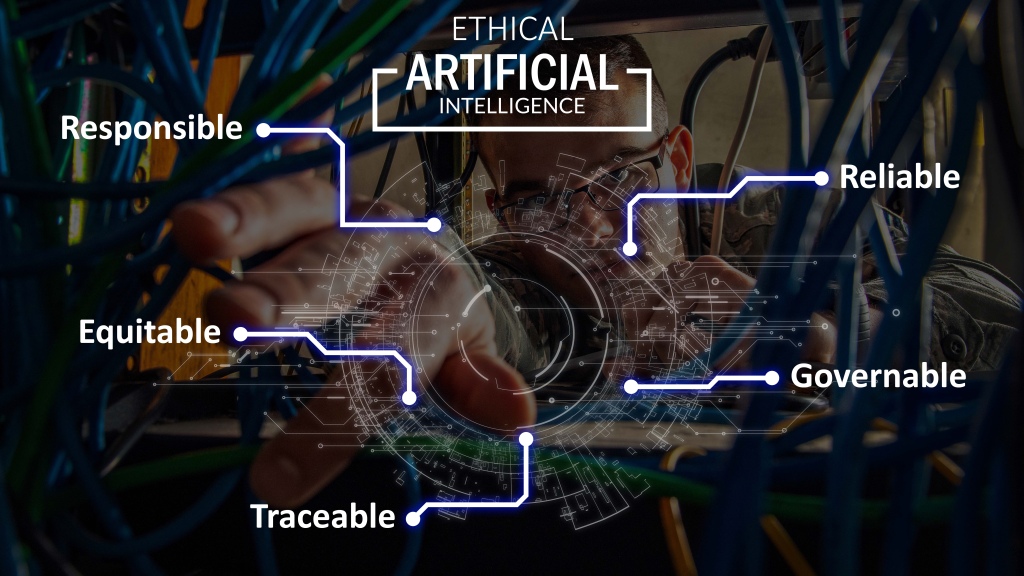

Bidirectional, Responsible Human-Machine Interaction

What I this piece is generally gesturing at, is that by integrating cybernetic technologies to seamlessly couple human cognition with increasingly advanced, generative computational tools, we can build a future where human intelligence is not replaced but expanded. It will be key for the designs to enable enactive, interactive, high-bandwidth communication that fosters mutual understanding and goal alignment. On this path, the future of programming isn’t obsolescence—it means transformation into a symbiotic relationship. By embracing collaborative, iterative human-machine interactions, we can amplify human intelligence, creativity, and problem-solving, unlocking possibilities far beyond what either can achieve alone.

Human-machine interaction is inherently bidirectional: machines provide feedback, solutions, and insights that we interpret and integrate, while humans contribute context, objectives, and ethical considerations that guide AI behavior. This continuous dialogue enhances problem-solving by combining human creativity and contextual understanding with machine efficiency and computational power. As we navigate this evolving technological landscape, focusing on responsible AI integration will be critical. Our collaboration with machines should aim to augment human capabilities while respecting societal values, goals, and, importantly, the well-being of all life.

As Norbert Wiener put it:

“The best material model for a cat is another, or preferably the same cat. In other words, should a material model thoroughly realize its purpose, the original situation could be grasped in its entirety and a model would be unnecessary. Lewis Carroll fully expressed this notion in an episode in Sylvie and Bruno, when he showed that the only completely satisfactory map to scale of a given country was that country itself” (Wiener, 1948).

True innovation lies in complementing the complexities of life rather than merely replicating them. In order to augment human intelligence, we ought to design our new technologies—especially AI—so as to build on and harmonize with the rich tapestry of human knowledge, the richness of experience, and the physicality of natural systems, rather than attempting to replace them with superficial imitations. Our creations are only as valuable as their ability to reflect and amplify the intricate nature of life and the world itself, enabling us to pursue deeper understanding, open-ended creativity, and meaningful purpose.

The ultimate goal is clear: to be able to design a productive connective tissue for human ingenuity that would seamlessly sync up with the transformative power of machines, and a diverse set of substrates beyond today’s computing trendiest purviews. By embracing and amplifying what we already have, we may unlock new possibilities and redefine adjacent possibles that transcend the boundaries of human imagination. This approach is deeply rooted in a perspective of collaboration and mutual growth, working toward a world in which technology remains a force for empowering humanity, not replacing it.

Allow me to digress into a final thought. Earlier today, a friend shared an insightful thought about how Miyazaki’s films, such as Kiki’s Delivery Service, seem to exist outside typical Western narrative patterns – a thought itself prompted by them watching this video. While the beloved Disney films of my childhood may have offered some great morals and lessons here and there, they definitely fell short in showing what a kind world would look like. Reflecting on this, I considered how exposure to Ghibli’s compassionate, empathetic storytelling might have profoundly shaped my own learning journey as a child – although it did get to me eventually. The alternative worldview these movies offer gently nudges us toward being more charitable. By encouraging us to view all beings as inherently kind, well-intentioned, and worthy of empathy and care, perhaps this compassionate stance is exactly what we need as we strive toward more meaningful, symbiotic collaborations with technology, and certainly with other humans too.

References:

- Biehl, M., & Witkowski, O. (2021). Investigating transformational complexity: Counting functions in elementary cellular automata regions. Complexity. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7501405

- Billinghurst, M., Clark, A., & Lee, G. (2015). A survey of augmented reality. Foundations and Trends in Human–Computer Interaction, 8(2–3), 73–272. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000049

- Dargan, S., Bansal, S., Kumar, M., Mittal, A., & Kumar, K. (2023). Augmented reality: A comprehensive review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 30(2), 1057-1080. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11831-022-09831-7

- Huang, J. (2023). Keynote Address at Computex 2023. NVIDIA Newsroom. https://youtu.be/i-wpzS9ZsCs?si=b4MQMwB3-on8zU21

- Lebedev, M. A., & Nicolelis, M. A. L. (2017). Brain-Machine Interfaces: From Basic Science to Neuroprostheses and Neurorehabilitation. Physiological Reviews, 97(2), 767–837. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00027.2016

- OpenAI. (2024). Learning to reason with large language models. OpenAI Blog. Retrieved January 15, 2025. https://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms/

- Pickering, A. (2010). The cybernetic brain: Sketches of another future. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8169881.html

- Rosenblueth, A., & Wiener, N. (1945). The role of models in science. Philosophy of science, 12(4), 316-321. https://www.jstor.org/stable/184253

- Smart Kid Abacus Learning Pvt. Ltd. [@smartkidabacuslearningpvt.ltd]. (ca. 2022). 12th National & 5th International Competition held in Pune [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved February 22, 2025, from https://youtu.be/YtFK5Dl-bww?si=-XS164m4LnrC4L5N.

- The Soak. (2024). Why Ghibli succeeds where Disney fails [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4xUaZ9Vr-Cg

- Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

- Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or control and communication in the animal and the machine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262537841/cybernetics-or-control-and-communication-in-the-animal-and-the-machine/