Scroll, Snack, Repeat

We live in a time of information abundance. It has become as plentiful—and as carefully engineered to exploit our every weakness—as modern processed food. The more content is optimized to manipulate our attention, the more our cognitive patterns are hijacked. Digital platforms are not only distracting; they reshape what we pay attention to and how we think.

The same cognitive patterns that once helped us survive by seeking vital free energy and novelty, now keep us locked in cycles of endless scrolling, technostress, and mental malnutrition. Worse, the more these systems optimize to capture our engagement, the harder it becomes to find truthful, nourishing ideas for the growth of humanity. Are we witnessing the edge of a Great Filter for intelligent life itself?

Overcoming this challenge will demand either drastically augmenting our cognitive ability to process the overflow of information, developing a brand new kind of immune system for the mind, or rapidly catalyzing the development of social care and compassion for other minds. Perhaps at this point, there is no choice but to pursue all three.

Digital Addiction and Mind Starvation in the Attention Economy

This post was inspired to me by brilliant science communicator and author Hank Green’s recent thoughts on whether the internet is best compared to cigarettes or food (Green, 2025)—a brilliant meditation on addiction and the age of information abundance. Hank ultimately lands on the metaphor of food: the internet isn’t purely harmful like cigarettes. It’s become closer in dynamics to our modern food landscape, full of hyper-processed, hyper-palatable products. Some are nutritious. Many are engineered to hijack our lives.

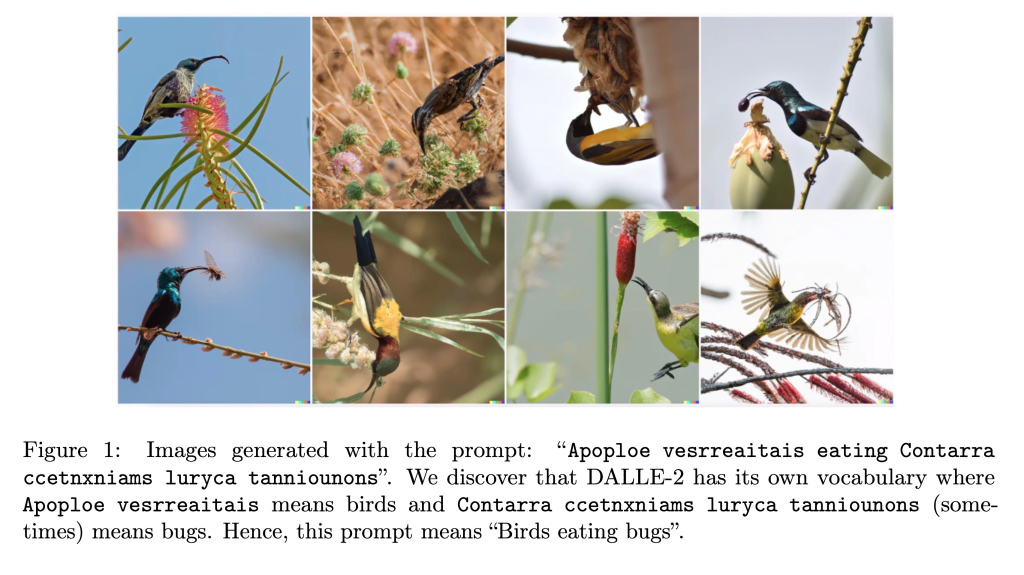

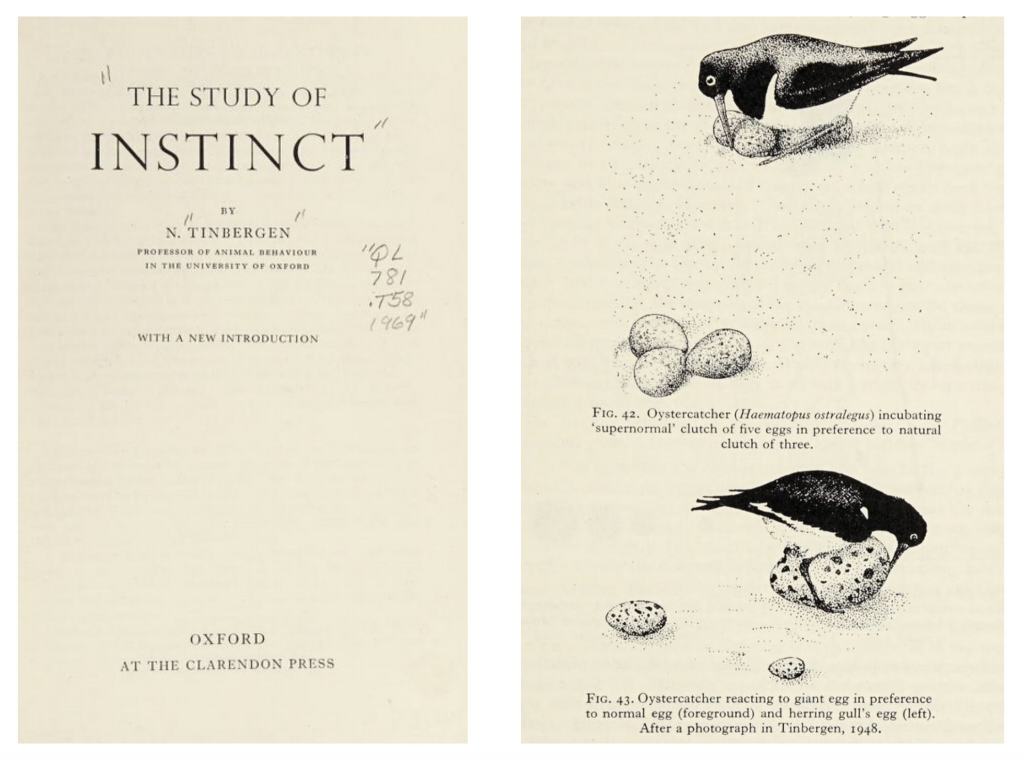

This idea isn’t new. Ethologist Niko Tinbergen, who won the 1973 Nobel Prize in Biology, demonstrated that instinctive behaviors in animals could be triggered by what he coined supernormal stimuli—exaggerated triggers that mimic something once essential for survival—using creatively unrealistic dummies such as oversized fake eggs that birds preferred, red-bellied fish models that provoked attacks from male sticklebacks, and artificial butterflies that elicited mating behavior (Tinbergen, 1951). Philosopher Daniel Dennett (1995), pointed out how evolved drives can be hijacked by such supernormal stimuli, and how our minds, built by evolutionary processes to react predictably to certain signals, can thus be taken advantage of, often without our conscious awareness. Chocolate is a turbo-charged version of our drive to seek high-energy food, which we come to prefer to a healthier diet of fruits and vegetables. Nesting birds prefer oversized fake eggs over their own. Cuteness overload rides on our innate caregiving instincts to respond powerfully to cartoonish or exaggerated baby-like features such as large eyes, round faces, and small noses. Pornography exaggerates sexual cues to hijack evolved reproductive instincts, ending up producing stronger reactions than natural encounters.

And here we are with the internet. For most of our biological history, we have evolved in a world of information scarcity, where every piece of knowledge could be vital. Today, we turned into the central lane of the Information Age highway, pelted by an endless storm of content engineered to feel urgent, delicious, or enraging (Carr, 2010; McLuhan, 1964). It’s not that infotaxis—meant in the pure sense of information foraging, like chemotaxis is to chemical gradients—is inherently bad. It can be as helpful as Dennett’s food, sex, or caretaking-related instincts. But the environment has changed faster than our capacity to navigate it wisely. The same drives that helped our ancestors survive can now keep us scrolling endlessly, long past the point of nourishment. As Adam Alter (2017) describes, modern platforms are designed addictions—custom-engineered experiences that feed our craving for novelty while diminishing our sense of agency. Meanwhile, Shoshana Zuboff (2019) has shown how surveillance capitalism exploits these vulnerabilities systematically, capturing and monetizing attention at an unprecedented scale. And before that, pioneers like BJ Fogg (2003) have documented how persuasive technology can be designed to influence attitudes and behaviors, effectively reshaping our habits in subtle but powerful ways.

This is the core problem we face: the more these systems optimize for engagement, the harder it becomes to access truthful, useful, nourishing information—the kind that helps us think clearly and live well. What looks like an endless buffet of knowledge is often a maze of distraction, manipulation, and empty mental calories. In other words, the very abundance of content creates an environment where the most beneficial ideas are the hardest to find and the easiest to ignore.

Defending Global Access to Truthful Information

Shall we pause for a moment and acknowledge how ridiculously challenging it has become to search for information online? Some of us can certainly remember times and versions of the Internet in which it wasn’t all that difficult to find an article, a picture, or a quote we’d seen before. Of course, information was once easier to retrieve because there was less overwhelming abundance, and part of this is due to the increasing incentives to flood us with manipulative content. But beyond simply the challenge of locating something familiar, it has also become much harder to know what source to trust. The same platforms that bury useful information under endless novelty also strip away the signals that once helped us judge credibility, leaving us adrift in a sea where misinformation and insight are nearly indistinguishable.

So how do we adapt? I think we have three broad paths. One is to augment our cognitive capacity—to build better tools, shared knowledge systems, and personal practices that help us sort signal from noise. This practice relies on an open field Red Queen’s race between mental cyberattacks for advertisement and protective systems trying to figure out how to transmit information. It’s not impossible. Just costly—to the extent it may render this way nonviable. This is the path of cryptography.

The second is to bury the signal itself. We can hide cognitive paths, and the channels we really use to communicate survival information with each other or within our own bodies, through a collection of local concealment strategies and obfuscation mechanisms. Even our body’s immune system, rooted in the cryptographic paradigm (Krakauer, 2015), works by obscuring and complicating access to its key processes to resist exploitation by external—as well as internal—parasites. Biological processes like antigen mimicry, chemical noise for camouflage, or viral epitope masking do involve concealment and obfuscation of vital information—meaning access to the organism’s free energy. Protecting by building walls—which means exploiting inherent asymmetries present in the underlying physical substrate—can incur great costs. In many cases, making information channels covert, albeit at the expense of signal openness and transparency, can be a cheaper tactic. This second path is called steganography.

The third and final path is to increase trust and care among humans—and the other agents, biological or artificial, with whom we co-create our experience in the world. Everyone can help tend each other’s mental health and safety. Just as we have learned to protect and heal each other’s bodies, we will need to learn to protect each other’s minds. This means allowing our emerging, co-evolving systems of human and non-human agents to develop empathy, shared responsibility, and trust, so that manipulative systems and predatory incentives cannot so easily exploit our vulnerabilities. This was the focus of my doctoral dissertation, which examined the fundamental principles and practical conditions by which a system composed of populations of competing agents could eventually give rise to trust and cooperation. The solution calls for reimagining the architectures of our social, technological, and economic institutions so they align with mutual care, and cultivating diverse mixtures of cultures that value psychological safety at an individual and global level. This is the path of care, compassion, and social resilience.

We’re only beginning to build the cultural tools to deal with this. Naming the dynamic—seeing how our attention gets manipulated and why it makes truth harder to reach—is the first step. Maybe the question isn’t whether the internet is cigarettes or food. Maybe it’s whether we can learn to distinguish empty calories from real sustenance, and whether we can do it together—helping each other flourish in a world too full.

Overcoming Mental Cyberattacks with Tools for Care and Reflection

I’ve seen people throwing technology at it: why don’t we use ChatGPT to steward our consumption of information. I’m all in favor of having AI mentor us—it holds many values, and I’m myself engaged in various projects developing this kind of technology for mindful education and personalized mentorship. But this presents a risk, which we can’t afford to ignore: these new proxies are so, so very susceptible to being hijacked themselves. Jailbreaks, hijacking, man-in-the-middle attack, you name it. LLMs are weak, and—take it from someone whose training came from cryptography and is spending large efforts on LLM cyberdefense—will remain so for many years. Actually, LLMs haven’t even gone through the test of any significant time like our original cognitive algorithms have—our whole biology relies on layer on layer of protections and immune systems shielding us from ourselves—from self-exposition to injuries, germs, harmful bacteria, viruses and harm of countless sorts and forms. This is why we don’t need to live in constant fear of death and suffering on a daily basis. But technology is a new vector for new diseases—many of which unidentified.

Credit: Jamie Gill / Getty Images

We need to learn to deal with such new threats in this changing world. The internet. Entertainment. Our ways of healthy life. How we raise our children. The entire design of education itself must evolve. We need new schools—institutions built not just to transmit knowledge but to help us develop the discernment, resilience, and collective care needed to thrive amid infinite information. It’s no longer about preparing for yesterday’s challenges. It’s about learning to navigate a world where our instincts are constantly manipulated and where reflection, curiosity, and shared wisdom are our best defenses against mental malnutrition. It’s time to work on incorporating care and reflection in our technolives—acknowledgedly, we can’t not recognize our lives are going to be technological too, and we also need to accept it and focus on symbiotizing with the technological rather fighting it—which requires in turn to help catalyze a protective niche of care and reflection-oriented technosociety around it. Let’s develop a healthcare system for our minds.

DOI: 10.54854/ow2025.07

References

Alter, A. (2018). Irresistible: The rise of addictive technology and the business of keeping us hooked. Penguin.

Carr, N. (2020). The shallows: What the Internet is doing to our brains. WW Norton & Company.

Dennett, D. C. (1995). Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (No. 39). Simon and Schuster.

Fogg, B. J. (2002). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Ubiquity, 2002(December), 2.

Green, H. (2025, June 28). You’re not addicted to content, you’re starving for information [Video]. YouTube.

Krakauer, D. Cryptographic Nature. arXiv 2015. arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.01744.

McLuhan, M. (1994). Understanding media: The extensions of man. MIT press.

Tinbergen, N. (1951). The study of instinct. Oxford University Press.

Zuboff, S. (2023). The age of surveillance capitalism. In Social theory re-wired (pp. 203-213). Routledge.